Churches Conservation Trust Annual Report

For many years now, Minerva Stone Conservation has enjoyed

working on behalf of the Churches Conservation Trust. Having cared for

fifteen or so churches we never tire of working for the Trust; each church

with its unique vernacular style, character and intriguing use of local

materials, each one offering a different social and historical insight,

some are architectural marvels, some not, but all are shrines to human

experience.

For many years now, Minerva Stone Conservation has enjoyed

working on behalf of the Churches Conservation Trust. Having cared for

fifteen or so churches we never tire of working for the Trust; each church

with its unique vernacular style, character and intriguing use of local

materials, each one offering a different social and historical insight,

some are architectural marvels, some not, but all are shrines to human

experience.

Our work encompasses problems affecting the structural integrity of a church

and more delicate conservation work on church monuments, architectural

details and carvings. We also address the more routine work of general

maintenance, for example clearing and painting gutters, painting railings,

rehanging churchyard gates, repairing damaged doors or window frames and

many other small improvements.

Learning and understanding a range of craft skills in the bench mark of

many modern craftsmen. The current approach towards repair requires that

many different small scale interventions are needed on a typical CCT project,

this generally requires the services of a good all rounder. Since 1986

the SPAB has organised a unique six month training programme (the William

Morris Craft Fellowship) in building conservation for young experienced

craftsmen and women. This helps to foster a broad appreciation of and respect

for materials and techniques outside the range of one’s craft. There is

also a growing demand for highly trained craftsmen who understand the wide

range of skills and methods used in historic building conservation projects

who can then can also bring together more specialised craftsmen or women

and manage projects with an understanding and empathy towards the task

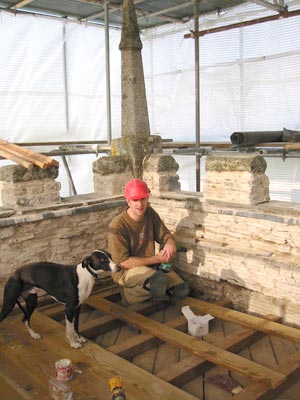

required. Most projects require convergence of craft trades. For example

the recent rebuilding of a spirelet (photo) brought together conservation

and steel replacement by our blacksmith (Tom Franklin, also trained in

stone conservation), replacement of the oak and lead onion on which it

sits and a new-carved finial (by Jason Battle) in Hartham Park limestone.

Langport Church in Somerset is a good case study of our work for the Trust.

The church is noted for its many elaborately carved Blue Lias wall monuments

on which we prepared a conservation report and proceeded with appropriate

conservation measures to those in most need of care. This involved stabilising

with cramps and using lime to consolidate surfaces that were were cracked

or friable. The church’s large and intricately carved reredos required

micro-pinning to reattach broken elements and some gentle cleaning.

However the bulk of work on this project was to carry out extensive mortar

repairs to the delicate hamstone tracery and mullions of the windows. In

many places, elements had eroded so badly that they had to be pinned with

copper wire and resin. As conservators we constantly have to face the dilemma

of when to replace instead of repair stonework. Hamstone mullions are a

case in point, because of easily eroded clay seams and awkwardly thin quarry

bed thickness the majority of hamstone now encountered is beyond conservation.

In 90% of the cases that I have worked on, medieval masons through necessity

fixed mullions in a vertical instead of a horizontal bedding plane which,

over time, leads to the natural failure and literal splitting of the element.

Repair is generally not suitable because of the shearing forces that would

be exerted on the pins, dowels, mortars & resins that would have to

be used.

Simple replacement elements such as mullions are produced

by our apprentices. At college they are taught to create near perfect pieces,

(Ruskin would not have approved - perfection does not arise from the natural

state of things). Although understandable in new works, this approach is

not entirely appropriate in dealing with several hundred years of movement,

tracery that no longer plumb with the cill, idiosyncratic medieval masonry

and recent bad quality repairs. The greater challenge is in creating a

replacement piece that fits perfectly, apparent for the apprentice and

accordingly difficult to price!

Simple replacement elements such as mullions are produced

by our apprentices. At college they are taught to create near perfect pieces,

(Ruskin would not have approved - perfection does not arise from the natural

state of things). Although understandable in new works, this approach is

not entirely appropriate in dealing with several hundred years of movement,

tracery that no longer plumb with the cill, idiosyncratic medieval masonry

and recent bad quality repairs. The greater challenge is in creating a

replacement piece that fits perfectly, apparent for the apprentice and

accordingly difficult to price!

One of our most satisfying projects for the Trust was at the little church

at Luffincote in Cornwall. Examination of the render on the tower identified

large problem areas. Its exposed position above the valley of the Tamar

meant that the render was under constant attack from the elements and was

in a sorrier state than had been thought. Therefore patching and repair

of the existing render was an inadequate response and it was decided to

remove all the existing render which had been applied some fifteen years

previously and replace it with a different mix and technique. Originally

the render had been trowelled or floated on but it was decided to "throw" the

new render on and then scrape the surface with a trowel when it had achieved

an initial set to get a rough, open finish. Although used in elsewhere

in the UK, Andrew Sharland my partner in Minerva picked up this technique

from craftsmen in Romania where he had been working with the Mihai Emenescu

Trust. This method overcame any difficulty in getting the render to stick

to the relatively smooth, keyless slate walls. The force of the throw compresses

the mortar, lessening shrinkage later on and, since slate is not very porous,

there is not enough suction between stone and mortar to make using a float

easy. The finished, limewashed tower should hold off the rain and wind

for a good few years. When the tower was complete we then shifted inside

where we lime plastered the south wall and limewashed the whole interior.

.